Author:

Max McLean

Published by Classic Melbourne on 4 November 2015

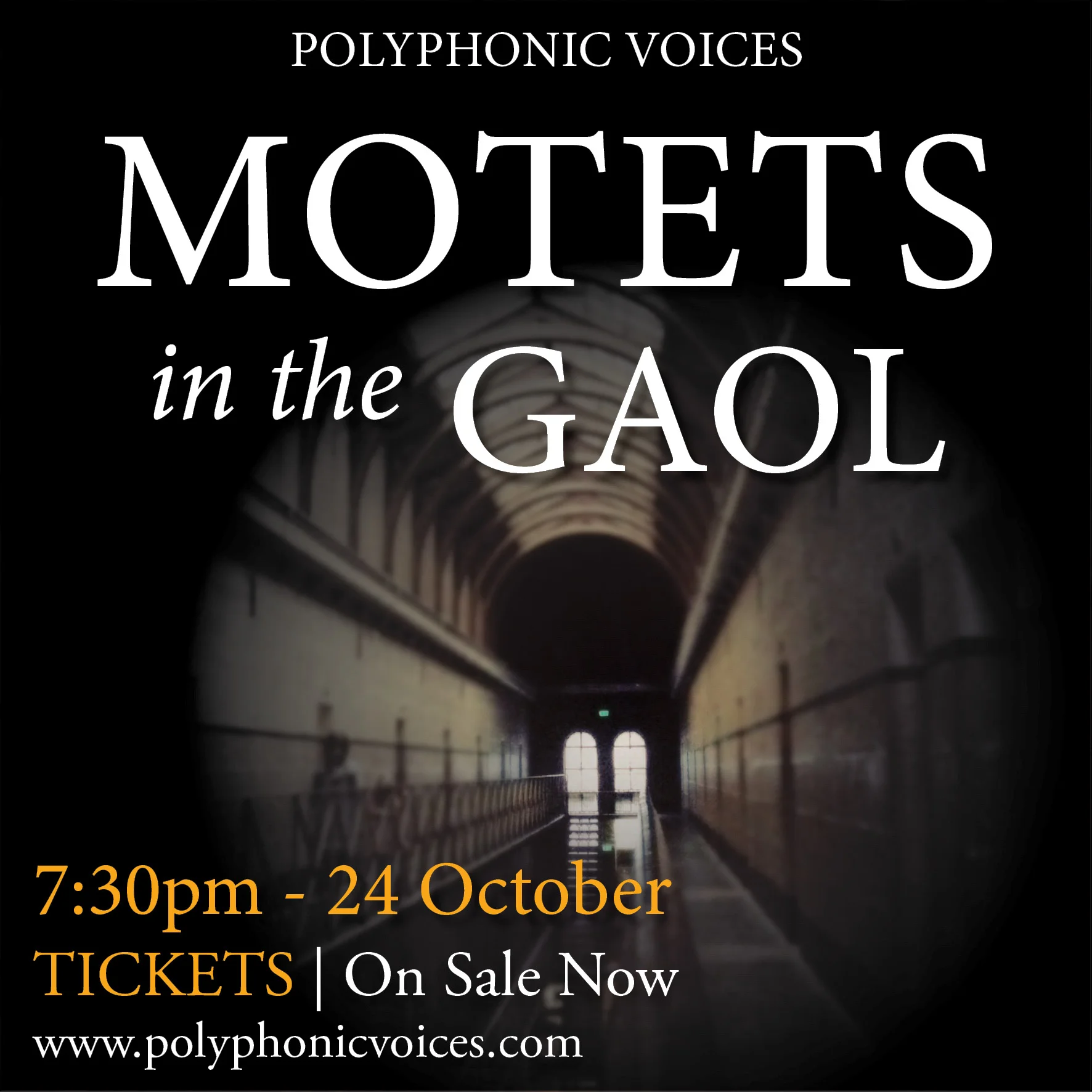

Midway through their performance of motets in the Old Melbourne Gaol, Polyphonic Voices’ Director of Music, Michael Fulcher, turned to the audience to explain what they were doing there. Acknowledging the gaol’s excellent acoustic, he also spoke of the venue’s accumulated grief and hoped the choir’s singing would mollify the suffering that had occurred there through the ages.

No longer assured of the communion with flock that choirs had in the churches or cathedrals for which these works were originally composed, choirs have been obliged to establish their own rationales for performance as the secularisation of the modern western world has progressively denatured the performance of sacred choral works.

It’s a credit to these relative newcomers on the Melbourne music scene that they are seeking meaningful ways to maintain connection with the unique spiritual force that comes from a group of people singing as a single entity. Polyphonic Voices is a 20-strong chamber group, instigated by university college choir graduates who wanted to keep singing together, bolstered by singers from parish choirs around Melbourne.

As well as the narrow but very long block of seating down the centre of the gaol floor, the choir also offered the unique option of sitting on cushions inside the tiny cells. Here the choir was out of view, but audience members could experience the music in a more solitary and meditative way.

The audience was invited to arrive early to inspect the gaol and its parallels with a church or cathedral were immediately apparent. For those who have never seen Old Melbourne Gaol, it is very much like a cathedral, very long and narrow and three tiers high, with a very high vaulted ceiling. Where the crucified Christ might hang in a church, here there is a scaffold as the chief focal point, which no doubt served both a symbolic and an all too practical disciplinary function in the gaol.

Old Melbourne Gaol now serves as a tourist attraction and along with macabre 3D death masks of some of the Gaol’s more infamous guests staring out at you from within glass cases in their cells, it is also rather brightly lit. It was no doubt a liability issue – isn’t everything these days – but the lights stayed on throughout the concert, which somewhat undercut the atmospherics. There was a small window at the top of the rear wall and it would have been wonderful to experience the gaol gently sliding into darkness throughout the performance as the daylight faded.

The concert’s opening seemed to take a few people by surprise, as, without lights dimming, voices suddenly appeared from above. The choir was hidden away on the very top tier, with only the Director of Music visible, on a gangway across the first tier.

The concert began with a motet, O beatum et sacrosanctum diem, from the early 17th century, by the English composer, organist and Catholic priest, Peter Phillip. It was celebratory in nature and the choir immediately made their mark with a full-bodied performance at a cracking pace that was crisp in articulation and on point throughout.

Setting a pattern that was to continue through the night, the choir changed position for each motet and so moved into view for a second motet by Phillips. With both ground level and two tiers to play with, the choir took full advantage of the acoustic effects they could achieve by their positioning.

Allegri’s famously ethereal Miserere mei, Deus not only came to the audience from above but the soprano soloists were separately located above and behind the audience, giving their contributions an even more disembodied quality. It worked to brilliant effect and the soloists were impressive. In contrast, the choir descended to ground level for two motets by JS Bach, which, along with the choir’s hearty performance and a cheery little organ accompaniment, emphasised the more earthbound, localised nature of the Lutheran congregations he composed for.

The program encompassed some 400 years of motet composition, from the Renaissance to today. Rather than take a chronological approach it freely moved across the ages and back again, contrasting renaissance works by Phillips and Gregorio Allegri with motets by a variety of contemporary composers, with works by Bach and Bruckner interposed for good measure.

Throughout the program, the choir displayed absolute technical security and stylistic coherence. The voices were solid from top to bottom, with the deeper voices coming into their own for Karl Jenkins’ Ave verum corpus. In his Ave Maria which followed, the staccato delivery on the words “Ave” and “Jesus” and the interweaving of voices throughout the motet were impeccably delivered and again at a fairly brisk pace.

With Tomas Luis de Victoria’s beatific Salve Regina, the idea of the choir as sonic smudging stick, cleansing the jail of its accumulated horror and despair, was particularly convincing. With the bruised sonorities and dynamic extremes of Bruckner’s Christus factus est the cleansing became more like a fully powered exorcism – this is a choir not afraid to sing loud.

Similarly, the choir brought the Ave Maria by contemporary Polish composer Pawel Lukaszewski to astonishingly full peaks of sound, before dying away to beautifully soft humming vocal effects from the male voices.

I did wonder if sometimes tempos were fractionally too pushed and occasionally wanted the spaces between the sounds to linger a little longer, but in every other respect this was an extremely satisfying concert – thoughtfully conceived and programmed, and executed to a very high standard. I look forward to seeing what they come up with next.